One reason the Laser Tag story has stuck with me was its setting in my home state of Florida. Being a native, I’ll admit that we do have our share of strange people and places. The state has a bit of everything and is probably the biggest microcosm of America outside of New York City. And across all of that hot, muggy, flat land in central Florida, are locales that can defy all logic and reason. We have no “typical” tourist traps here.

CreepyToys was just one of the more recent message boards I’ve scoured (and the only I moderated). I visited many more back in my more social internet days—early web, like the mid-nineties, when the etiquette thing was still in its infancy and if you owned a successful message board, you were a rock star.

There was a smaller one I happened upon, which I’m sure is also long gone by now. It was meant to attract fellow Floridians and their offbeat tales and experiences. I visited every so often, more as a lurker, never really posting because my boring life didn’t lend much to share. The main forum was the place where users posted their real life strange stories that happened anywhere in Florida, whether they lived here or were just visiting. Emphasis was placed on the “real” aspect, but of course, you can say anything you want on the web. I’m sure many posts were less than truthful (now we’d call most of them trollfics).

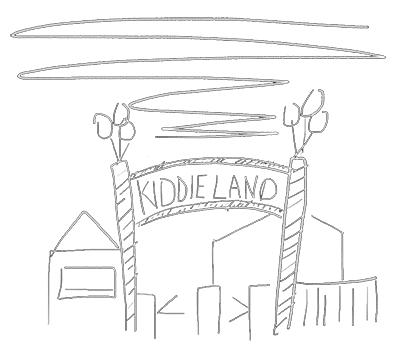

During a 3 A.M. reading session one night, my eyes locked onto a thread title, specifically on two of its words. It was written by a girl my age I will simply call “Kate”. She posted “Anyone remember Kiddie Land?” And upon seeing the name of this place, some dark recess of my memories lit up. Somehow, I already knew it was a location, and not some TV show, or book, or something else.

“I think I visited a place called Kiddie Land when I was young. For some reason I forgot all about it until just recently. Maybe it was in central Florida? My parents used to take me all over the state. Dad was a photographer who liked to take pictures of all the weird little theme parks and such that dot the interstates (can that be plural?) and highways. I remember most of them clearly, which is kind of a feat when you got, you know, the big ones like Disney World and Universal Studios overshadowing all the smaller parks.

“What’s weird is that if I concentrate, I can still get clear memories of most everything from the Weeki Wachee mermaids to Dinosaur World, but this Kiddie Land thing, not so much. It must have been incredibly lame, judging by its name alone. It was probably some sad little park that didn’t leave much of an impression. So why am I thinking about it so much all of a sudden? Why, when I look through all of my dad’s photo albums, do I not see its sign anywhere? He would shoot anything, and always the front gates. Was this place even real?”

I scrolled through the replies as I tried to get a grasp on these forgotten memories that were trying to wriggle up to the surface. Most of the responses were useless as far as answers or similar experiences went, save for one, by a boy also our age. I’ll have him go by “Jack”, always a winner cover name.

“You’re joking. I thought I was going crazy back in the third grade when I talked to other kids about it! I had also forgotten it for a while. Creepy. I think it was a crappy place. I kind of just remember getting mad at Dad for not letting me do the bumper cars because I was too young. The only other thing I can really say was that its mascot was maybe a Florida panther or something.”

I wanted to reply back then, but I didn’t have anything to contribute, yet. And sure, it was strange that this place seemed to be a memory that we had all forgotten and later remembered to some degree and struggled to clarify, but that’s not uncommon for childhood recollections. We all have places, events, television shows, movies, and other things stored away somewhere, so fuzzily that we wonder if they actually existed or not.

But Kiddie Land stayed with me, more persistently than any other recalled memory I’ve had. After a few days of thinking about it and trying to dig up a single solid image in my mind, I asked my sister if she remembered it at all. She’s two years younger than me, so I didn’t expect that she did. Even so, she did end up helping me in a way—one of her first memories was of Cinderella’s Castle at Disney World. After some mulling, that later gave me a time and place.

I asked my dad soon after, also not expecting much. Parents take their kids to a lot of places, and I knew he wouldn’t remember some dumpy old theme park that I probably didn’t have any fun at, either. He didn’t even try to recollect such a place, not that I had high hopes to begin with.

He changed after the car accident. I say that only barely knowing what he was like before it happened. And up until now, I had only two steady memories of that entire year: Disney World, and my mom’s funeral. I guess that I tried to bury the latter, and never really sorted out that the accident actually happened on the way back home from the resort. Of course anything in between those two moments would have been lost in immemorial oblivion.

We lived in Ocala, a town northwest of Orlando, for one more year before we moved. I was seven when we left. We had only filled two photo albums since then, mostly of vacations and birthday parties. There were far more tucked away in the attic, dusty and unopened for years. I went through them and saw plenty of baby pictures and a few of my first day at kindergarten, but I didn’t find any taken at Disney World. I kind of knew I wouldn’t—Dad wouldn’t have added them considering what happened. I found that he didn’t even have them developed. But luckily, there were also two unlabeled, undeveloped rolls of film in the box. I hoped that time and the attic’s heat hadn’t ruined them.

They came out very red and a bit splotchy when I had them developed, but they were for the most part readable pictures. As I looked through two rolls worth of Mickey’s place circa 1990 prints, filled with happy background kids, lots of smiles from my sister and I, and a fine collection of late 80’s clothing, I tried to keep my emotions in check and focus on looking for any kind of clues.

For the most part, it was all just evidence of a regular summer vacation. But I did take away one thing from the images: it had been a rainy weekend. There were puddles on the ground in many pictures, and water droplets clearly visible on the Dumbo ride. What really brought back memories of that trip was the one snapshot of six year old me looking sadly out at the gray clouds from our hotel room balcony. They were also the last proof that my dad was a happier man once, as few times as he appeared in the pictures.

Remembering how our parents were always eager to keep us happy, I realized that even if we managed to go on most of the good rides in between showers, they would’ve seen our disappointment and given us one last stop on the way home; a last ditch effort to correct a nearly ruined vacation.

It was then that a smell hit me, accompanied by a visual. I could see a food stand, with an old man handing me a hotdog. I could taste the aroma, and that scent of rainwater on a hot summer’s day, evaporating in the sun… I could see the puddles on colorful, swirling tile, surrounding a ticket booth.

I was sure now that this place was real, or at least had been once. Dad was never able to remember it, the few times I asked again. I didn’t know if he even tried. After all, it was just hours later, with him behind the wheel…

The old scar on my side itched. Twenty-eight stitches.

I soon stopped thinking about it as the last years of high school took hold. I would still try occasionally, usually before I went to sleep, to pull out more memories, images, and reasons for that place—but my mind had gone quiet.

I didn’t get my driver’s license until after I graduated, and it was really only so that I could get myself to college. During my first year, after I began to feel confident in my driving ability, I took two separate trips to and back from Orlando and my old house in Ocala. One drive was on the interstate; the other, longer one was where I took the back roads. I looked for billboards, old signs, and even made a few stops at dilapidated gas stations and rest stops where I looked through the oldest tourist brochures I could find. No references.

These trips were out of the way and wasted an entire day, so I didn’t try a third time. With college assignments and social life to attend to, my quest for Kiddie Land fell further onto the back burner, sometimes to the point where I forgot about it all over again. But in 2008, it resurfaced once more.

When I was a kid, I was a self-proclaimed Lego master. I got my interest in architecture early, and loved to build. Looking for pictures of interesting houses, stores, skyscrapers, and sure, even amusement parks at times was a hobby of mine. Civil engineering on a bigger scale also grabbed me, and starting with the old SimCity games, I got myself hooked on the layouts of cities and roads, and loved looking at or creating maps in general.

I guess it suited me, being a logical and analytical type—despite my love for a good urban legend or scary story. Wanting to step into the world of urban planning and cartography, I took a job as a county surveyor after college. It’s as menial as you’d expect, and sometimes the drivers going past you as you work shoot glares, probably because they just don’t get what we’re doing when we’re out there staring at the landscape through our total stations like dorks.

But at least I got to go somewhere new most days, and a part of me was figuring that this experience might be valuable for tracking down whatever remained of the enigmatic park. Even then, I did still want to answer the nagging question of what became of the place.

My work didn’t provide much entertainment, so I used my nights to map out the center of the state, covering a wide area. At my disposal were things I didn’t have before on my initial journey for information, such as GPS, Google Maps satellite images, and quick access to a wide array of historical data. The biggest asset I had was my refined critical thinking, which gave me the ability to map the odds of Kiddie Land having existed in any given area. I wanted to steadily whittle down its possible locations until I had a short list.

To no surprise, the internet provided no direct answers to its existence. I assumed that it had been destroyed or closed long before modems entered our houses, and as no nearby newspaper had any stories of the place, I also inferred that it was far from any town or city. It must’ve been in the middle of nowhere, a true roadside attraction almost too strange and non sequitur to exist.

After weeks of digging, I stumbled upon Kate once more. At first, I didn’t know it was her Tumblr page (during the site’s earliest days), which was a photo blog of odd attractions throughout Florida, with some places from out of state mixed in as well. As far as photographic subjects went, she really took up her father’s mantle. But I might have passed her by if it wasn’t for a single post she had made, around the beginning of her page’s creation.

She had taken a picture of an abandoned front gate of a local, small amusement park somewhere in Arkansas. The sign was colorful and cheery, yet utterly decrepit and about ready to rot away completely. And it was somewhat familiar, a fact that Kate had also picked up on as evident by her comment on the image. After reading it, I decided that it was finally time to contribute.

She had written, “This sign reminds me of Kiddie Land, closer to home. Not that anyone would remember it. But I swear it was real!”

I soon got in touch with her, and we began exchanging emails. At first, she was happy to hear from a fellow Florida kid, but she didn’t actually believe that I also had memories of the park. She had kept in light correspondence with Jack over the years, and despite working together, they apparently never heard from anyone else with recollections. So I could understand her skepticism. And I felt crappy that I hadn’t said something ten years ago.

Jack had moved out of state, but his interest never left him. Soon the three of us were like old friends, catching up. We had many long nights together, three-waying in private chat rooms. We were all Florida 90’s kids with similar interests, and we talked about a lot more than Kiddie Land. It was nice just to connect with people who grew up within a hundred miles of me. We became good friends, and over the months, we synchronized all that we knew about the park—however little that was—and began to focus more on theories.

My “mad geography skills,” as Jack put it, helped establish a probable, much smaller range of where Kiddie Land could’ve been, in turn making them feel a little less delusional in their belief that it was real. Before I came along, as far as they knew, it could’ve been anywhere in the state.

They still had contributions of their own and shared with me years of work. Both were more sociable and outgoing than I was, and had spent the last decade visiting library archives, calling people who could’ve had some possible connection to the park, and researching all manner of tax codes, construction, land ownership, and the business of theme parks. But they gave up several years ago, because boredom had triumphed over intrigue. The two lived a few counties apart and never met, and Jack moved to Georgia six months ago.

Without a single adult to legitimize the park’s history, like a former staff member or parent of a visiting child, I could see why they had done what they could to research the place under constant doubt. And while Kiddie Land hadn’t taken over any of our lives, it was a powerful enough “force” to sometimes disrupt them. We agreed to continue our work until we could at least prove or disprove the park, so that we could move on, free of its lingering presence.

After months of chatting, in late 2008, we decided to meet each other in person. We chose a chain restaurant off of I-75 in the north. Before then, I had never even met in person any online friends I had ever made. It was a strange, new experience for me. But they both seemed pretty normal.

We met, sat, ate, and talked for over two hours. We tried to keep it light hearted, focusing more on getting used to each other before going on a nearby nature walk for some seclusion and diving into our shared topic of interest.

Jack was a year younger than me, and a gamer and eternal teenager. He worked from home and even won money from online game tournaments. Though his lifestyle was basically a walking archetype, he was also very creative and both a programmer and lover of “fine” science fiction. He believed that he had visited the park in 1992, the latest of the three of us.

Kate was the tallest, and had confidence to go along with her height. The rimless glasses that hovered over a few freckles gave her an air of maturity, and she was certainly the most accomplished among us, having served on the ground at MacDill Air Force Base in some technical position; I wasn’t sure how high up she was or what she did exactly. I didn’t want to pry. She had a soft center though, and a love of adventure. And as a photographer, she carried her camera everywhere. She also visited the park in 1990, but in December.

On our second go around on the nature trail, we began speaking a little more personally with each other—and that was when we learned of some ominous shared, similar stories that cast the mystery in a darker light.

All of us had personal tragedies that happened around the time of our park visits. Specifically, shortly after we came to and left Kiddie Land.

I spoke first, really only mentioning in passing about how we were hit by a drunk driver that had spun off of an on-ramp, right into our car, probably within an hour of leaving the park. It was something I rarely shared with people, but I was at the point when I wanted to search out any other possible connections.

And I had found one. We stopped on one of the boardwalks above the nature trail’s marshland, and soon Jack was telling us about how he lost both of his maternal grandparents perhaps the night after his visit, to a house fire in Daytona Beach. He was closer to them than he was to his own parents, who, according to him, “never cared for me much.”

But I think Kate’s story was the most tragic. When she was six and her older sister was eight, they took a week off to visit every theme park in the state that they could find. They wanted lasting family bonding time, as Kate’s sister had advanced leukemia. She was confined to a wheelchair, but Kate could recall that she still enjoyed the trip even more than she did.

Somewhere along the way, before heading home, they must have gone to Kiddie Land together. But again, for whatever reason, her father never took any pictures of the place. Kate’s sister soon after experienced complications and died a week later in hospice care. Her family was never the same.

None of ours were after our separate tragedies. We had all fundamentally changed in our young lives, maybe grew up a little faster than most kids. And the idea that a backwoods park seemed involved… It changed our perception.

Jack was the first to blurt out what we were all thinking: that Kiddie Land was a cursed place, a bringer of misfortune. I think he just wanted to change the tone of the uncomfortable conversation; he seemed adverse to real-life’s harder events. But I knew we had all briefly entertained that very idea.

Kate soon had another take, and made a good point. Her sister had suffered through cancer for years and was on a clear decline during her last few months. The park couldn’t have caused her illness. There was no reason to assume it was somehow responsible for a house fire or car crash either.

We decided not to waste the day driving around the state or even just my defined probable area looking for remnants. We knew the odds of actually seeing anything of the park by now were just too small. Instead, after dinner and before Kate and Jack started their long journeys home, once our minds were clear again following the earlier emotional discussion, we tried forming a collective visual of the park—maybe even a map, if we were able. I could certainly help with that.

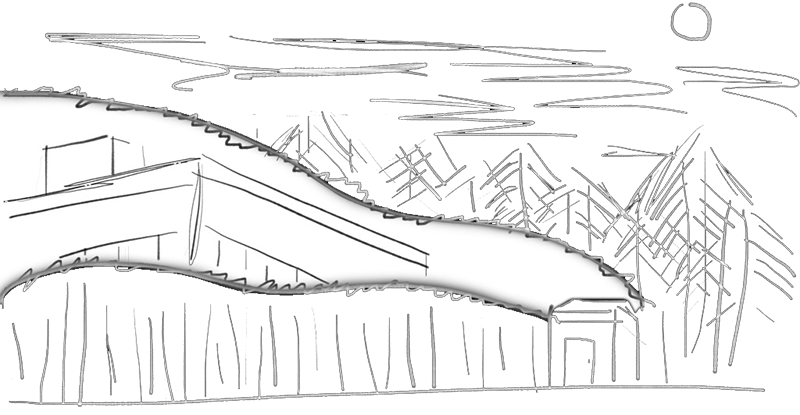

So, what did we know, or at least thought we knew? We started with the basics: the size, colors, and shapes of the park. Then we moved onto rides, and the people we remembered seeing there. All of our memories were hazy and scattered, so probably none of them were all too accurate. Even so, after hours at a restaurant table that we occupied right up near closing time, I had made the first known visual representation of the place; a simple sketch.

There were missing, blank spots, and the known rides were likely not in their correct locations. Still, we all agreed that my sketch was actually, eerily, similar to what few images remained tucked away in our heads. The front gate was colorful and simple, with painted balloons floating up wooden posts up to an old cast iron marquee. The words “Kiddie Land” were painted to look like they had been written in chalk. Oddly, while we could form a solid consensus of the gate, everything inside the park became less vivid, and more debatable.

Jack thought there was an old merry-go-round with wooden horses. Kate and I both remembered a small rollercoaster meant for children, like the kind you’d find at a county fair that might’ve had a crappy dragon’s head painted on its front. We all agreed that there was definitely a bumper car rink, where the cars were maybe painted like bugs. Aside from a possible petting zoo, fun house, and inner tube-filled small pool, the only other things we could really recall were a few food and toy stands and bathrooms. We surmised that the land was likely no bigger than a typical department store. Amusement parks were always good at disguising their size, appearing larger when you’re in them.

We even guessed that tickets were probably around three to five bucks for children. It did, after all, sound like a quaint place, not much more than a permanently active “mom and pop” small town Florida fairground.

They both took pictures of the sketch with their phones, and satisfied, at least for now, we all headed to our homes, back to the real world.

Weeks went by, and we hadn’t talked online much since our get together. I scanned my sketch and sent it to Kate, who posted it on her blog just for fun, and maybe to see if anyone had any reactions to it. To kill time, I began casually researching amusement park lore, and some urban exploration on the side.

Places like Disney’s Discovery Island and River Country, both closed down and with reputations of their own, really started to fascinate me. And there were people that managed to get inside parks all over the world that had been left to decay, many of them small and once independently run. I was able to visualize myself, exploring a rotting Kiddie Land, taking pictures, proving it was real…

Then, on the first night of winter, I got a call from my sister, who still lived in the same town as our dad. She was incredibly upset, and I had to force her to tell me what was wrong. Through her tears, she told me the bad news.

Our dad had killed himself, just hours ago. His depression had been out in the open for many years, but he always seemed to at least manage to get by day after day. Maybe it was simple being lonely that finally drove him to end everything. Naturally, we both felt guilty in different, multiple ways.

I offered to drive down and be there for her, but it was already one in the morning, and she insisted that I come in the morning. My sister was always a strong and independent person, so I was sure she was handling things all right. Before she hung up, she sounded uneasy, and like she had something else to say. But she knew that it wasn’t the right time.

Just before I awoke in the morning, when I was still addled by sleeping pills, I had a short, but very vivid dream. I was walking in Kiddie Land. And I saw everything. It didn’t even feel like a dream it all; it felt like a real memory, either returning to me, or somehow… being born, right as I was experiencing it.

The moment I was up, I got to work. I wrote down what I had seen on my phone, and had the “dream” cycle around in my mind many times, in my attempt to memorize and grab hold of it tightly. I saw the rides, I saw other kids and the staff, I saw faces—I even tasted the ice cream. I could feel the warm sun, just as I could “feel” the color; strangely, I could sense each color and how vibrant they were, and yet, it all looked washed out, like a Polaroid photo. I had no doubt that the sudden recurrence was the sharpest the three of us had ever experienced.

And then I remembered what had happened last night, and where I had to be. I made the two-hour drive back to my second house trying my hardest not to think of the park. I had much more important things to tend to today. I didn’t even consider that I was now an orphan until I was going down the last off-ramp.

I spent a week back home trying to get it all over with. I spoke with family members on my dad’s side that I hadn’t seen in years. A few of my mom’s relatives were there too. I didn’t know how to act, really, so I survived the days on autopilot and let everyone else do the talking. I found that a suicide brought a kind of stigma, a shared regret that loomed over everything and made the proceedings feel heavier than other funerals. Christmas didn’t exist that year.

My sister spent most of her time with her husband and baby daughter. I kept mostly to myself, and sort of drifted through the house, trying to recall the good times the three of us had here together. Not that there were many.

On the last day of my visit, I went up to my old room and sketched out a more refined version of Kiddie Land before I forgot that dream entirely. It was as if I had seen the entirety of the small park in my head that morning through a series of flashes. With some guesswork, I was able to create a fairly decent map with all the rides and paths. Only the top middle of the park was blank. It looked like something should logically go there, in that spot between the rollercoaster and the pool, but I just couldn’t think of anything.

My sister came in once I was done. We talked about things, like what we would be doing with the house. We knew this meant that we were, in a way, “official” adults now, and our lives would be changing.

But just as I was thinking that maybe it was time to let go of Kiddie Land for good, she looked at my sketch, and her eyes widened just a little. She told me that she remembered the front gate, and the time long ago when I asked her about the park. She didn’t know why or how she could suddenly see its entrance in her head again, and though she had no images past it, she was positive that “the gate looked just like that.” I was once more locked in.

On the way back to my apartment, I wondered what else could be at work here, and my mind began to entertain more… supernatural explanations. Was it possible that something was triggering, or even creating memories, false or otherwise? Had something happened in our childhoods that made us this way? If another tragedy struck one of us, would we be afflicted again?

My sister was too young to create proper memories when we supposedly went to Kiddie Land. And as I threw more and more ever wilder explanations at myself, I settled on one idea that somehow felt entirely possible. What if I actually had no recollection of the park, until the moment of the accident? It’s already easy to forget the chronological order of your own life.

There was an email from Kate waiting for me when I got home. The number of Kiddie Landers had grown again, and our newest member was our youngest. I’ll call him Tyler, and he claimed to have gone to the park in 1993. He told us nothing else until our first chat room discussion, on New Year’s Eve.

While I had what the four of us saw as the earliest encounter with the park, Tyler claimed that he certainly had the last. Before we even got our introductions out of the way or learned anything about him, he shared with us how he remembered it. It was a very different kind of memory.

He was there when it burnt down. And furthermore, he thought he knew what road it was once on, or just off of. Coming out of nowhere after seeing the posting of my first sketch, he changed everything with a few messages.

“Anyway, about Kiddie Land… I grew up with divorced parents. Every other weekend, my dad would pick me up and take me to his house out in the boonies. We used State Road 40. That was pretty much the ONLY central Florida road I traveled as a kid. I’ve done research on my own for a while. BTW, for some reason, I don’t remember actually pulling into the park.

“So, I guess I’m kind of reclusive. And I’ve been following Kate online for a few months. That probably sounds creepy. I was there when it was burning, in what had to be 1993. I would’ve been five. My only memories are of it being on fire. People were screaming. They were on fire too. Even the kids.”

None of us had responded yet. I should have told the others beforehand my theory of the memories possibly being somehow false.

“But I don’t see anyone die. And my parents aren’t there. They all just run away as everything burns. Also, all I do is walk, like I’m not scared of any of this. Had therapy for a while. The guy got me convinced that it was just a recurring dream. I’m sure again that it isn’t. Scary part is, the memory makes me feel happy. Like a part of me enjoys watching it burn. So when should we meet?”

We decided to take it slow with Tyler. And I didn’t think Jack appreciated his apparent fondness for fire, considering the nature of his ‘memory trigger.’

Tyler’s revelation of the right road to be looking at—and his own story of how he remembered the place—already gave us enough to think about for the night. But I went ahead and divulged my theory that the park wasn’t even real; that it was a false memory that we all somehow had embedded into us, and it was activated when we suffered a personal disruption of childhood.

But he was different. Unlike the rest of us, his life had been mostly uneventful. Furthermore, his only images of the park came to him in vivid dreams. He couldn’t even remember times before he dreamed about it.

While they were intrigued by my theory, I wanted to cast off any doubt about its possibility, so I shared my recent occurrence. I told them that it couldn’t have been a coincidence that I saw Kiddie Land again the morning after I learned what my dad had done. At first, my friends’ only responses, aside from condolences, were how I was more concerned about the park than my family.

I told them that I wasn’t obsessive—that this was just something I had to share. I was still grounded in reality, I wasn’t thinking about the park all the time.

Only, I realized that at this point, I was. And what I asked the three to do next only emphasized my steady spiral down into obsession. I wanted us to get together within a week or two, while Tyler, a college student, was still on winter break. He was close by and didn’t mind, but Kate and Jack argued that they had just been with me, and had better things to do.

I told them I’d pay for their expenses, that it would only be for a day or two, and that if we didn’t find anything, I’d drop it. I went on about how close we were now, how we could “end” things. Amazingly, I managed to convince them. In hindsight, I had touched the boundaries of raving lunacy. I guess in that moment, my passion to solve the mystery finally ran over the brim.

A week later, during the early January doldrums, our group met at a small airstrip in the morning. It was a cool, clear day, and we’d be able to see for miles and miles. Knowing that it was now or never on finding any remnant at all of Kiddie Land, I had decided to go all out and hired a pilot to fly us through the middle of Florida in a small plane, or at least the length of State Road 40.

As much time as I had spent on satellite maps looking for prospects, I wanted to see the entire area for myself—hoping that one of us would have a kind of eureka moment upon seeing a specific plot of land from the air. It was expensive, but I had some inheritance coming my way. Kate and Jack obviously thought I was crazy for going this far, but they still got into the plane.

Tyler was hard to read. He was… strange. When we first saw him pull up and get out of his ancient Toyota, all we saw were two small, dark eyes looking at us from under a gray hoodie. He didn’t say much at first, and although he did eventually warm up to us, I often caught him staring at me, as if studying me.

Our small, two-engine plane flew from Ocala to the east. The pilot didn’t ask what we were trying to see more than once, and we got a good view of the national forest on the way. He kept us as low and slow as possible, and I took many pictures of the roads. We all kept our sight on the landscape below, Tyler especially. We figured anything strange might either stand out in the swaths of trees, or be covered up by them, and remain lost forever.

At one point, Tyler suddenly turned and looked out of the right side. I felt compelled to as well—as did Kate and Jack once they saw that we were fixated on something. They leaned over us and saw that a few miles away was a square patch of dirt not far from State Road 40, just off of a smaller forest road heading south. The land was free of trees and looked like a construction site of some kind. It was just big enough for a small theme park.

With not much on the horizon, I marked the location on a map, and asked the pilot to turn around and land. I felt that there was no reason to go further out; if that spot wasn’t what we were looking for, we wouldn’t find another.

Back on the ground, we got in my car and I drove us out there. On the way, I asked Tyler what he thought. I had to refrain from asking him something more mystical, like if he “felt” anything, although at this point I wouldn’t have been surprised if he did. He still seemed invested, but Kate and Jack were clearly losing what little interest remained. I couldn’t blame them. They had put in more work and time in chasing after this place than I ever had, until just recently.

Deep into the national forest and with no other cars around for miles, I slowed, stopped, tried to sense anything “off” about the area, and then turned onto the southbound road. My palms sweaty on the wheel, I drove just another quarter mile, found the currently empty construction site, and pulled off the road. We all got out. I started taking pictures right away, of dirt.

It was quiet and lonely out here, with nothing around but the faint sounds of nature in the thick layers of trees. The others were unimpressed, and the area didn’t exude any sort of feeling other than isolation. We walked into the square of earth where trees had been cleared, and the only signs of human presence were mover tracks and sparse litter. We didn’t see anything out of the ordinary, and the land was unmarked. It didn’t look like they were putting a building of any sort out here; Kate assumed that it might be a parking lot later for park visitors. The plot of land was no bigger than a typical department store’s.

Every fifteen minutes, either Kate or Jack asked if we could leave now. I asked for another extension each time—and in any case, we had only taken my car, so they would have to wait until I was satisfied. Tyler at least had shown some genuine fascination as he sized up the place, though he kept to his usual silent self and began to give me strange looks again.

I didn’t know what we should be looking for, or if this was even the right spot. Still, we hunted for a bit of everything. Foundations, bricks, buried toys, trees growing around an old fence or lamppost. We searched for old garbage that would have survived, like soda lids, plastic toys, and metallic ride remnants such as springs and screws, We scoured the nearby trees for toppled signs, and kicked dirt away to maybe reveal ticket stubs or maps. If there ever was a small theme park out here, there should have been some lingering evidence of it.

By the time the sun began dipping under the treetops, we had run out of water, energy bars, and motivation to keep searching. Kate and Jack looked like they never wanted to think about Kiddie Land again. I personally wanted to keep up the “quest,” with or without them. But as I was thinking about where to look next and got ready to go back to my car, Tyler shouted out to us.

We followed his distant voice until we caught up with him, deep in the woods. He had found a lonely utility shed. It was little more than chipped blue paint, cinder block, and an aluminum roof and door. At its side, partially buried under pine needles, was a sturdy concrete foundation with four holes drilled into its top where something had once been anchored to the ground.

The small structure had been obscured by the trees and impossible to see from the road or construction site. After some quick visual measurements, I could tell that it was lined up to the center of the dirt square—the same spot on my Kiddie Land sketch that I couldn’t map out.

With Kate and Jacks’ interest rekindled, we worked together to pry the door open and stepped inside. The windowless interior was not much bigger than a walk-in closet, but without the walking space. Rusted barrels, rotting wooden crates, and boxes of old light bulbs and tools covered nearly every inch from the dirt-covered floor to the moldy ceiling. Faded white stencil writing was still legible on a few of the containers, but they were only serial numbers of some kind and wouldn’t give us any clues. There was a single light fixture that burnt out long ago, but there was still something else quietly powered in the shed.

Every few seconds, a faint chirp-like beep came from the back, from some place buried under the forgotten equipment. Kate had never heard a sound quite like it, but figured that it was most likely a simple radio transponder; information could still be broadcasting to a shady corporation or government agency.

Knowing that an inexplicable force had driven four Florida kids to come all the way out to a strange shed in a forest, we worked to clear it out and find the source of the beeping. If we couldn’t take out or open the device, we would at least get tons of pictures and do whatever it took to find out just what it was, and who was connected to it. At that point, we all must have felt vindicated, assured that we were all sane and had the fortune to be in on something very exclusive, secretive, and potentially life-changing.

Kate tossed out one last empty barrel that had been stacked in the corner, and then there it was: a dented, ugly, 1960’s era cabinet that looked like a fuse box and had four steady green lights, with one blinking amber that lit up when the box let out its digitized chirp, just as it had been doing tirelessly for decades, if not longer. The padlock was badly damaged and brown with rust. After waiting briefly to take a few pictures and to ask Kate if she thought it was safe to force open, I took one of the old nearby hammers and bashed it.

The padlock broke off under a puff of iron dust, and the compartment door creaked open. We all squeezed in close to get a good look. Inside was a bizarre set of analog dials, switches, glowing dots of light, capacitors, and the thing that stood out the most—a small, green phosphor computer monitor.

It measured only about five inches, was built all the way into the cement wall behind it, and had no apparent inputs. Whatever kind of information it once kept was gone, but it and the computer it was hooked up to were somehow still operating. A single blinking text cursor even now awaited a command.

I felt like we had seen more than enough, and my gut was telling me that it was time to leave—that we shouldn’t have come here in the first place. The other three were astonished by what we had found, but I knew that whatever it was we had truly been looking for once sat on the foundation outside, and that this radio beacon was only a fragment of what went on here.

As my want—my need to simply go home grew, I went outside and searched for a cable, or some clue of how this shed was powered. The others were too enamored by the antiquated tech inside. Both Kate and Jack were studying the box and transmitter, and already arguing about their origin.

I couldn’t explain it, but I was starting to feel a deep, primal fear similar to what I had experienced moments after the accident. It was as if the device was still broadcasting a signal that made my very memories feel vulnerable; I became afraid that I’d suddenly lose them, or have them tampered with again. I was then desperate to end an obsession that had grown steadily for over a decade.

I never found the power source for the shed, so I did the only thing that made sense. I took one of the empty metal barrels that we had tossed out, and charged in like a madman. I smashed the transmitter first, and with every ounce of my strength, ran the barrel into the compartment. The tiny monitor’s glass shattered, sparks flew, and a capacitor caught on fire.

I expected Kate and Jack to flip around, shout at me, and demand that I explain why I had just done such a thing. But they simply kept staring at the equipment even though it was broken, ignoring me entirely. Only Tyler looked at me, with just a tinge of surprise. And then I felt my head exploding.

The worst pain I had ever felt ripped through my skull, and I ran from the shed and back out onto the construction site. All I could think about was the aspirin in my car, as if it would do anything to quell such a headache. I stopped moving as soon as I left the trees, and saw… something.

There was a rip in space, moving like a flag on a windy day. All throughout the area, I could see fragments of what looked like another world, or another time. A part of me knew by instinct that it was all in my head, but I still couldn’t convince myself that it wasn’t real.

The tear grew quickly. Beyond was the same forest, but with different patterns of trees, of different sizes. The world separated itself from mine by way of its colors—they weren’t as rich; they had lost much of their saturation.

The dimension grew and spread across the ground. A fenced parking lot appeared, and then an entire building. It was a two-story facility, with tinted windows and no lettering. The few cars in the lot, all black sedans, were made no later than the early 1990’s. The building had a large satellite dish on its roof.

I felt lightheaded, close to passing out. I quickly spun around and caught a very brief glimpse of the shed. It was still surrounded by trees, but there was a pathway leading to it. And nearby, on the cement foundation, was a metal radio tower that just barely stood taller than the forest’s tree line.

As my hearing devolved into a loud buzzing, I lost consciousness and hit the ground. Although I had seen parking lot asphalt under me, I remember landing in dirt shortly before blacking out entirely into a dreamless sleep.

I awoke in a hospital in Ocala, about twenty-five miles away. It was just like waking up on any other day, without pain. A nurse came in and told me that I had been out for two days. My sister arrived first. We didn’t talk about Kiddie Land at all, though she did wonder how I ended up so far away, in such a lonely place. As we spoke over the course of an hour, I began to feel that something was off. It was like I had lost time, that some part of me was missing.

Then Tyler came in, still dressed in his gray hoodie. As he told me what happened, I picked up that he remembered the experience differently than I had. I asked him where Kate and Jack had gone, and if they were okay.

My sister asked him who Kate and Jack were and looked at Tyler. He only shrugged. I told him he had been following Kate online. He denied it.

I asked about the shed. He told me that we found nothing out there but a patch of dirt. Shortly after arriving, I stared into space for around five minutes before collapsing. I was unresponsive, and he managed to get me here.

My heart raced. I had no idea what had just happened to me, or what was real, if anything. Memory had betrayed me. How many years had I…

I asked him about Kiddie Land. He looked at me oddly, and reminded me that the whole reason we drove all the way out there was to find it. My sister told me that I had been talking about it for a while now. Eventually Tyler believed my amnesia excuse and summarized a reality that been lost to me.

He told me that we got in touch after he saw the first version of the park sketch that I had posted on my Tumblr blog. I wanted to respond that while I had one, it was neglected; I never posted anything. My best course of action was to only listen and accept, since I was the one in the hospital bed. Not long after I made the better, truer second sketch, we met and set out. We still took a plane, although it was just the two of us. My credit card bill confirmed this.

Over time, I came to terms that I had somehow screwed up my memory after going to that site, which had affected me in a way that it hadn’t for Tyler. But I wasn’t convinced that he was free of tampering either, if he couldn’t recall the shed. I didn’t know what had actually happened, and I don’t think I ever will.

I think that my memories were altered again the moment I attacked the machine. Everything that had happened before that instance concerning Kiddie Land was a skewed version of truth, some of it real, some of it fictionalized in a way that led me to believe I had come across the site in a different manner.

But regardless of what knotted, mangled version of personal history now existed in my head, something didn’t add up about Jack, and to a greater extent, Kate. I only got involved in everything after seeing that one picture of hers.

Before I left the hospital, I used my phone to find her blog. It was still there, along with that image of a park in Arkansas. I knew Jack was real too. Only, I had never spoken to him, and I had never contacted Kate, either. I then showed Tyler her page. He looked a little dumbfounded at first that I had been worrying about the safety of someone not even involved with our story.

Then he asked me why I had never gotten in touch with her.

As I checked out, my mind was busy trying to sort through what might have really happened, and what was translated into a subtly changed reality that helped guide me to what could be some big existential self-fulfilling prophecy. Maybe some invisible third party led me to that shed. Without my memories intact, it’s an impossible task to explain everything.

Before I parted ways with Tyler, he pulled me aside as my sister sat in my car and waited for me in the driver’s seat. He shared something that made the Kiddie Land saga even more confusing and foreboding.

He stared at me the way he did earlier because he remembered me from his dream. As everything burned, I stood in the center of the park, smiling. But I wasn’t my six-year old self. I was an adult, just as I was now. He had grown up wondering about the identity of that man, and seeing me in person only brought up more questions. I didn’t know what say at first. I was overloaded by then.

In the end, I only asked him if he thought I destroyed the park. No, he told me. He always had the impression that I had created it. And yet, I was glad to see it burn to the ground. But after listening to my description earlier of things that never happened, he now had a distrust of his own past, and told me not to dwell on it too much. Sure enough, I couldn’t help it.

I returned to the construction site days after going home, on my own. There was no shed or tower base, but the ground where they had been was torn up. I could only deduce that something had been recently removed.

Things went back to normal after that. I worked, I slept, I ate, and I browsed the web. I never had any more vivid recollections of the park designed to come to children who needed a good childhood memory. I could only ever recall the slowly fading images that came back to me at sixteen.

A few years ago, I pulled out the old family photo albums again and went through them. I did a double take on one image, flipping the page back after realizing that I had seen something strange in its background.

I had to have been five when it was shot. I was on the carpet, in my pajamas and smiling. The flash had been used, so while I was lit up, everything else was for the most part in darkness. But the plastic Lego blocks behind me reflected enough light to show up, at least partially.

Some time before that weekend trip, I had made a front gate out of different colored blocks, with room for the rest of an amusement park on the green construction plate behind it. Scribbled messily in marker, on paper taped to the sign, were the words “Kiddie Land”.

After several weeks of wondering and worrying about what it all meant, I thought about the friends I had once thought I made. Maybe in this reality, they weren’t tired of the mystery yet. Other than the sketches and my unexplainable Lego photo, I didn’t have pictures to share—since I never really took any.

But I did have the most unbelievable story of my life, and that gave me a better place to start than “last time.”

I checked to see that Kate’s photo blog was still active, and then sent her the map of a quaint Florida amusement park.

I decided that it was finally time to contribute.

And one last thing.

https://www.google.com/maps/@29.1725703,-81.7552685,620m/data=!3m1!1e3

(It’s a parking lot now.)